Category: Forensics / Reverse Engineering Difficulty: Hard Points: 500 Author: muffin

Download: Challenge Files

---

Description

She is not of Lordran’s timelines, nor any world scholars recall. An unbound Firekeeper caught between files that refuse to load and geometry that rejects her shape, as if she were written into existence and erased in the same breath.

Only fragments of her remain, scattered through the wreckage of an unfinished realm:

Those who examined the fragments recall a single whisper threaded through all anomalies:

“To restore her, trace the fragments. All three converge where the last bonfire never burned.”

Ashen Shard

A brittle sliver from a world that failed to load. A silhouette flickers within it, suspended between one form and the next. It remembers where she once stood, though the world does not.

Cinder of the Rogue Machine

A smoldering ember taken from a dormant construct. It mutters in recursive tones, as if trying to recall a name long lost. It burns not with flame, but with computation.

Bone of the Lost Reflection

A pale remnant from a body that never fully resolved. Its surface trembles with faint afterimages of a kneeling figure. Some say it holds her final memory.

Objective

Recover the three fragments hidden across the provided materials. Reconstruct the forgotten path of the unbound Firekeeper. Assemble the final key where a bonfire should have been, but never was.

Solution

PART-1

Challenge: We are given a Havoc Engine dump file. Objective: Locate the Firekeeper.

Initial Analysis

We are provided with a large set of files from the game dump. To start, it’s crucial to understand and reverse-engineer the Havoc Engine and how it loads the game’s proprietary formats.

FromSoftware uses custom, proprietary files for game data. As a result, traditional tools may not work directly, and you’ll often need your own utilities to parse or modify these files.

Notes:

- Tutorials for Dark Souls Map Studio generally apply to Smithbox, although some UI elements and workflows have changed.

- Older tutorials use Yabber, which is now outdated and may cause problems. Instead, you should use WitchyBND, which works similarly for most users.

Modding Considerations

It’s important to note that FromSoftware games were never designed to be modded.

There are primarily two types of mods that can be loaded via mod loaders: DLL mods and file replacement mods.

DLL Mods

- Contain primarily a

.dllfile. - May also include configuration files (

.ini) or other required resources. - Modify game memory directly, enabling effects that file replacement mods cannot achieve.

- Example: Seamless Co-op.

* Although it has its own folder and launcher, it can still be loaded via mod loaders alongside other mods.

File Replacement Mods

- Consist of modified versions of the game’s internal files.

- Common files and folders involved:

* regulation.bin, data0.bdt

* Directories: chr, parts, map, event,

msg, menu, script, param

- These mods replace in-game assets or behavior without directly modifying memory.

Approach

1. Explore the dump:

* Identify file types relevant to the Firekeeper (maps, characters, events). 2. Reverse Havoc Engine formats:

* Understand how .bdt, .param, .event and other proprietary files

are loaded.

3. Use proper tools:

* WitchyBND for extracting and modifying BND archives. * Smithbox for map-related analysis. 4. Locate the Firekeeper:

* Track character spawn data, event scripts, and map files to pinpoint her location.

Understanding file structure for file replacement mods

This is one of the most critical aspects of using mods, and something that many users get wrong.

Basically, all mod loaders expect the mod files that you add to be in a very specific structure, which mirrors the same structure used internally by the game.

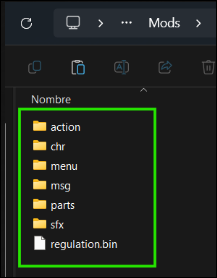

For example, below are screenshots of Clever’s Moveset Modpack being added both correctly and incorrectly to the Mod Engine 2 “mod” folder. This example is applicable to any other mod loader and game, not just ME2 and Elden Ring

This is correct and will work, because all these folders and the regulation.bin file are things that the mod loader is looking for, being part of the game’s internal file structure, and they are placed directly in the “mod” folder. In the case of ME3, it would be the equivalent “eldenring-mods” folder by default.

Before starting it it's important to identify what Game version the files are in ie # How to Identify the Game Version (Patch) a Mod Uses

| Category | Parameter | Description |

| ------------------------ | ----------------------- | ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- |

| Game Parameters | AIStandardInfoBank | Determines the parameters for enemy AI |

| | AtkParam | Determines hitbox and damage parameters for attacks |

| | BehaviorParam | Determines behavior parameters for triggering projectiles and attacks |

| | Bullet | Determines parameters of projectiles |

| | CalcCorrectGraph | Handles value curve functions for various mechanics |

| | CharaInitParam | Determines loadout parameters for Armored Core type characters |

| | CoolTimeParam | Determines cooldowns (abilities, actions, etc.) |

| | EnemyBehaviorBank | Parameters for enemy behavior and collision |

| | EquipMtrlSetParam | Material costs for various transactions |

| | EquipParamAccessory | Parameters for accessories |

| | EquipParamGoods | Parameters for goods |

| | EquipParamProtector | Parameters for equipment/armor |

| | EquipParamWeapon | Defines weapon types and affinities; affects scaling on consumables; special

effects can be modified via ReinforceParamWeapon |

| | FaceGenParam | Configuration of NPC faces |

| | GameAreaParam | Determines soul and humanity drops upon boss victories |

| | HitMtrlParam | Parameters applied when hitting various materials |

| | ItemLotParam | Determines contents of treasures and item rewards |

| | KnockBackParam | Parameters relating to knockback |

| | LevelSyncParam | Parameters for level synchronization |

| | LockCamParam | Parameters for player cameras |

| | Magic | Configuration of magic spells |

| | MenuColorTableParam | Coloring used for various interface elements |

| | MoveParam | Parameters for movement |

| | NpcParam | Parameters for enemy characters |

| | NpcThinkParam | Parameters for enemy AI thinking/decision making |

| | ObjActParam | Parameters for object interactions |

| | ObjectParam | Parameters for objects |

| | QwcChange | Parameters for world tendency changes |

| | QwcJudge | Parameters for world tendency effects |

| | RagdollParam | Parameters for ragdolls |

| | ReinforceParamProtector | Parameters for reinforcing armor |

| | ReinforceParamWeapon | Parameters for reinforcing weapons |

| | ShopLineupParam | Parameters for shops |

| | SkeletonParam | Parameters for character skeleton and foot IK |

| | SpEffectParam | Parameters for special effects |

| | SpEffectVfxParam | Parameters for particles triggered via SpEffect |

| | TalkParam | Parameters for character dialogues |

| | ThrowParam | Parameters for throws |

| | WhiteCoolTimeParam | Parameters for friendly phantoms cooldowns |

| Graphical Parameters | DofBank | Parameters for depth of field assignments |

| | EnvLightTexBank | Parameters for environmental lighting textures |

| | FogBank | Parameters for fog volumes |

| | LensFlareBank | Parameters for lens flares |

| | LensFlareExBank | Parameters for lens flares |

| | LightBank | Parameters for light maps |

| | LightScatteringBank | Parameters for light scattering |

| | LodBank | Parameters for levels of detail |

| | PointLightBank | Parameters for point lights |

| | ShadowBank | Parameters for shadow maps |

| | ToneMapBank | Parameters for tone maps |

--- First, start by unpacking the game using UXM. UXM allows you to patch the executable so the game can load loose files instead of reading directly from the packed archives. This is crucial because it enables file-level modding without permanently altering the original archives. After downloading UXM from its GitHub repository, select the game you want to mod (DS1, DS2, SotFS, DS3, or Sekiro) and let UXM unpack all game assets into a folder. The tool will also automatically patch the game executable, so it references the unpacked loose files during runtime.

Once the game is unpacked, the next step is to inspect and edit the PARAM files using WitchyBND. WitchyBND is specifically designed to handle FromSoftware’s archive formats, allowing you to unpack and repack .bnd and .parambnd files. Open WitchyBND, load the relevant .parambnd files from the unpacked game folder, and explore the various PARAM tables such as AtkParam, MoveParam, EquipParamWeapon, or NpcParam. Each table corresponds to different gameplay mechanics—attacks, movement, weapon properties, enemy behaviors, and so on. You can modify numeric values, affinities, cooldowns, or other parameters directly within the tool.

After making edits, you need to repack the PARAM files with WitchyBND so the game can read your modified values. It’s important to always back up the original PARAM files before making changes, in case anything breaks. Start by testing small modifications, such as adjusting one weapon’s stats or a single enemy parameter, to ensure the changes work as intended. Once you verify your edits, you can expand to more comprehensive adjustments, gradually customizing gameplay mechanics according to your design goals.

This workflow—unpacking with UXM, editing with WitchyBND, and repacking for testing creates a clean and manageable process for modding. The table of PARAM descriptions you prepared earlier serves as a quick reference for identifying which parameters to modify and which to leave untouched, helping you avoid unintended side effects while modding complex systems like AI behavior, weapon affinities, or environmental effects.

--- This method allows you to force object textures to load in any map for both PTDE and Remastered editions of Dark Souls. Normally, objects like bonfires or corpses already exist in multiple maps, so this technique isn’t required for them. However, for objects that appear in only one map and usually grab textures from that specific map rather than their own .bnd, this method ensures that they display correctly in other locations. Be aware that this process is a bit tedious and requires careful handling of multiple files.

Before you start, you will need the following tools: Yabber (for unpacking/repacking .bnd and .tpf files), a Flver Editor (for viewing and editing .flver model files), and the texture files you want to use.

Begin by fetching the object you want to use from its original map files (e.g., m10_01_00_00). Locate the object inside the map’s object folder (e.g., o1234.bnd) and extract it using Yabber. Inside the unpacked folder, you will find the .flver file (the 3D model) and potentially a .tpf file (textures). If the .tpf file is missing or empty, it means the object relies on the map’s global texture archive. In this case, you must locate the map’s texture references and extract the specific textures required by your object.

Next, you need to create a custom texture archive for your object. Create a new .tpf file using Yabber and import all the necessary .dds texture files into it. Once your .tpf is ready, repack the object’s .bnd file, ensuring it now contains both the .flver model and your new .tpf texture archive. This forces the game to load the textures directly from the object’s bundle rather than searching for them in the map files.

Finally, test your object in-game by placing it in a different map using Smithbox. If successful, the object should appear with all its textures correctly applied, regardless of which map it is loaded in. This technique is essential for creating custom map assets or porting objects between different areas of the game without relying on external texture overrides.

---

Patched Version:

csharp

if (param_1 != (void *)0x0) {

if (param_2 != 0) {

uVar1 = *(uint *)(param_1 + 0x18);

if ((uVar1 & 2) != 0) {

*(uint *)(param_1 + 0x18) = uVar1 | 0x4;

return;

}

}

}

return;

Remove All Checks for DS1:

csharp

void FUN_00100d30(void)

{

return;

}

GetMapMSB:

csharp

void FUN_00100d70(long param_1,long param_2)

{

*(undefined4 *)(param_1 + 0x58) = 1;

*(undefined4 *)(param_1 + 0x5c) = 1;

return;

}

---

PART-2

Running the binary

When trying to execute the binary, we face an immediate segmentation fault.

bash

./rust_vm_poc

[1] 1337 segmentation fault (core dumped) ./rust_vm_poc

This suggests either memory corruption or a deliberate anti-debugging/anti-analysis mechanism. Given the CTF context, the latter is highly probable.

File Analysis

Let’s start with a standard `file` command to identify the architecture.

bash

file rust_vm_poc

rust_vm_poc: ELF 64-bit LSB pie executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2, BuildID[sha1]=..., for GNU/Linux 3.2.0, stripped

It’s a standard 64-bit ELF executable, dynamically linked and stripped.

Strings Analysis

bash

strings rust_vm_poc_mangled

Critical Finding - Python C API Symbols:

Py_Initialize

Py_Finalize

PyRun_SimpleString

PyImport_ImportModule

PyObject_GetAttrString

PyObject_CallObject

...

The presence of these symbols confirms that the binary embeds a Python interpreter. This means the core logic likely resides in Python bytecode or a script executed at runtime, rather than purely in native assembly.

This is a strong indicator that we might need to extract Python bytecode later.

ELF Header Inspection

Since the binary crashes immediately, let’s inspect the program headers using `readelf`.

bash

readelf -l rust_vm_poc

Elf file type is DYN (Position-Independent Executable file)

Entry point 0x...

There are 0 program headers, starting at offset 64

Wait. "0 program headers"? That shouldn’t happen for a valid executable. This suggests the Program Header Table is corrupted or missing.

Looking at the ELF header:

bash

readelf -h rust_vm_poc

...

Start of program headers: 0 (bytes into file)

Size of program headers: 56 (bytes)

Number of program headers: 0

...

The e_phoff (program header offset) is 0, and the number of headers is 0. The kernel loader relies on these headers to map segments into memory. Without them, the loader fails to set up the process address space correctly.

Specifically, when `e_phoff` is zero (or points to an invalid location), the kernel reads nonsensical values for file offsets, virtual addresses, and permissions. As a result, during the loading process, it attempts to create invalid memory mappings, which immediately triggers a page fault. This leads to an instant segmentation fault before the program’s main() function or any initialization code runs. Because the crash occurs inside the kernel’s loading routine, traditional debuggers like gdb can’t attach in time to catch the fault, leaving the binary apparently “undebuggable.”

Since the loader depends entirely on the program headers to set up the memory space, repairing this field is necessary before further analysis or execution. The fix involves correcting the Program Header Table offset (e_phoff) in the ELF header. For ELF64 files, this value resides at byte offset 0x20 within the file. Using a hex editor, you can navigate to that position and replace the eight bytes representing 0x0000000000000000 with 0x0000000000000040 (the little-endian encoding of decimal 64).

Next step would be to write a solve script for the binary to patch the magic headers

python

import sys

import os

import struct

def repair_elf_header(filepath):

"""

Repairs the e_phoff field in a corrupted ELF header.

"""

# The e_phoff field is at offset 0x20 (32) in a 64-bit ELF file.

E_PHOFF_OFFSET = 0x20

# The correct value is 64, since the program headers start

# right after the 64-byte ELF header.

CORRECT_VALUE = 64

try:

with open(filepath, "r+b") as f:

# Go to the location of e_phoff

f.seek(E_PHOFF_OFFSET)

# Write the correct 64-bit integer value (64) in little-endian format

f.write(struct.pack('")

sys.exit(1)

filepath = sys.argv[1]

if not os.path.exists(filepath):

print(f"[!] File not found: {filepath}")

sys.exit(1)

repair_elf_header(filepath)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

Running readelf again gives us:

bash

21:12:47

ELF Header:

Magic: 7f 45 4c 46 02 01 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

Class: ELF64

Data: 2's complement, little endian

Version: 1 (current)

OS/ABI: UNIX - System V

ABI Version: 0

Type: DYN (Position-Independent Executable file)

Machine: Advanced Micro Devices X86-64

Version: 0x1

Entry point address: 0xf250

Start of program headers: 64 (bytes into file)

Start of section headers: 523080 (bytes into file)

Flags: 0x0

Size of this header: 64 (bytes)

Size of program headers: 56 (bytes)

Number of program headers: 14

Size of section headers: 64 (bytes)

Number of section headers: 32

Section header string table index: 31

Now we can start running the binary again , to see it's true behaviour

./rust_vm_poc Execution finished.

In the entry function we can see that

bash

0010f26f ff 15 2b CALL qword ptr [->::__libc_start_main] undefined __libc_start_main()

fd 06 00 = 001802d8

So this instruction is the usual way position independent executables call external library functions: the call goes through a GOT entry so the dynamic loader can patch it to the real address.

Also we see a main : ) So thats something , all the functions from the symbol table have been stripped so we manually have to trace back each call '

Lets take a look at main

c

/* WARNING: Type propagation algorithm not settling */

/* WARNING: Globals starting with '_' overlap smaller symbols at the same address */

undefined8 FUN_001125b0(undefined8 param_1,undefined8 param_2)

{

uint uVar1;

void *pvVar2;

int *piVar3;

long lVar4;

int iVar5;

pollfd *ppVar6;

__sighandler_t p_Var7;

ulong uVar8;

pthread_t __th;

long lVar9;

undefined4 *puVar10;

long lVar11;

int *piVar12;

int *piVar13;

undefined8 uVar14;

ulong uVar15;

undefined *ppuVar16;

int *piVar17;

pollfd *__fds;

code *pcVar18;

long in_FS_OFFSET;

bool bVar19;

int local_118;

int local_114;

void *local_110;

pthread_attr_t local_108;

ulong uStack_d0;

ulong local_c8;

ulong uStack_c0;

ulong local_b8;

ulong uStack_b0;

ulong local_a8;

ulong uStack_a0;

ulong local_98;

ulong uStack_90;

ulong local_88;

undefined8 uStack_80;

_func_5327 *local_78;

size_t local_68;

undefined8 local_60 [6];

piVar17 = &local_118;

local_108.__align._0_4_ = 0;

local_108.__align._4_2_ = 0;

local_108.__align._6_2_ = 0;

local_108._8_8_ = 1;

local_108._16_8_ = 2;

__fds = (pollfd *)&local_108;

pcVar18 = poll;

do {

iVar5 = poll(__fds,3,0);

if (iVar5 != -1) {

if ((((local_108.__align & 0x20000000000000U) != 0) &&

(iVar5 = open64("/dev/null",2,0), iVar5 == -1)) ||

(((local_108._8_8_ & 0x20000000000000) != 0 &&

(iVar5 = open64("/dev/null",2,0), iVar5 == -1)))) goto LAB_00112b18;

ppVar6 = __fds;

if ((local_108._16_8_ & 0x20000000000000) != 0) goto LAB_00112711;

goto LAB_00112730;

}

ppVar6 = (pollfd *)__errno_location();

uVar1 = ppVar6->fd;

} while (uVar1 == 4);

/* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

abort();

}

iVar5 = fcntl(2,1);

if ((iVar5 == -1) && (__fds = ppVar6, ppVar6->fd == 9)) {

LAB_00112711:

iVar5 = open64("/dev/null",2,0);

ppVar6 = __fds;

if (iVar5 == -1) goto LAB_00112b18;

}

LAB_00112730:

p_Var7 = signal(0xd,(__sighandler_t)&DAT_00000001);

if (p_Var7 == (__sighandler_t)0xffffffffffffffff) {

local_108.__align = (long)&PTR_DAT_0017e2f0;

local_108._8_8_ = 1;

local_108._16_8_ = 8;

local_108._24_8_ = 0;

local_108._32_8_ = 0;

uVar14 = FUN_00136cf0(local_60,&local_108);

FUN_00133cc0(uVar14);

FUN_0010e5a0();

LAB_00112aa3:

local_60[0] = CONCAT71(local_60[0]._1_7_,1);

local_108.__align = (long)local_60;

FUN_0010df40(&DAT_0017fa08,0,&local_108,&DAT_0017d4e0,&PTR_s_library/std/src/rt.rs_0017d4b8);

LAB_00112a10:

piVar12 = __errno_location();

piVar13 = (int *)0x0;

LOCK();

bVar19 = DAT_0017fad8 == (int *)0x0;

piVar3 = piVar12;

if (!bVar19) {

piVar13 = DAT_0017fad8;

piVar3 = DAT_0017fad8;

}

DAT_0017fad8 = piVar3;

UNLOCK();

if (bVar19) {

return 0;

}

if (piVar13 != piVar12) {

do {

pause();

} while( true );

}

FUN_00107710("std::process::exit called re-entrantly");

LAB_00112aea:

ppuVar16 = &PTR_s_library/std/src/sys/pal/unix/sta_0017e150;

}

else {

uVar8 = sysconf(0x1e);

local_108._32_8_ = 0;

local_108._40_8_ = 0;

local_108._16_8_ = 0;

local_108._24_8_ = 0;

local_108.__align._0_4_ = 0;

local_108.__align._4_2_ = 0;

local_108.__align._6_2_ = 0;

local_108._8_8_ = 0;

local_108._48_8_ = 0;

DAT_0017faf0 = uVar8;

__th = pthread_self();

iVar5 = pthread_getattr_np(__th,&local_108);

bVar19 = iVar5 == 0;

if (!bVar19) {

LAB_00112832:

local_88 = 0;

uStack_80._0_4_ = 0;

uStack_80._4_4_ = 0;

local_98 = 0;

uStack_90 = 0;

local_a8 = 0;

uStack_a0 = 0;

local_b8 = 0;

uStack_b0 = 0;

local_c8 = 0;

uStack_c0 = 0;

local_108._48_8_ = 0;

uStack_d0 = 0;

local_108._32_8_ = 0;

local_108._40_8_ = 0;

local_108._16_8_ = 0;

local_108._24_8_ = 0;

local_108.__align._0_4_ = 0;

local_108.__align._4_2_ = 0;

local_108.__align._6_2_ = 0;

local_108._8_8_ = 0;

local_78 = (_func_5327 *)0x0;

sigaction(0xb,(sigaction *)0x0,(sigaction *)&local_108);

if ((pollfd)local_108.__align == (pollfd)0x0) {

if (DAT_0017fb00 == '�') {

DAT_0017fb00 = '';

/* try { // try from 001128a0 to 00112986 has its CatchHandler @ 00112b44 */

DAT_0017faf8 = FUN_0014f930();

if (iVar5 == 0) {

puVar10 = (undefined4 *)malloc(4);

if (puVar10 == (undefined4 *)0x0) goto LAB_00112b2c;

*puVar10 = 0x6e69616d;

FUN_00134b20(pcVar18,ppVar6,puVar10);

}

bVar19 = false;

}

uStack_80._0_4_ = 0x8000004;

local_108.__align = (long)FUN_0014fb00;

sigaction(0xb,(sigaction *)&local_108,(sigaction *)0x0);

}

sigaction(7,(sigaction *)0x0,(sigaction *)&local_108);

if ((pollfd)local_108.__align == (pollfd)0x0) {

if (DAT_0017fb00 == '�') {

DAT_0017fb00 = '';

DAT_0017faf8 = FUN_0014f930();

if (bVar19) {

puVar10 = (undefined4 *)malloc(4);

if (puVar10 == (undefined4 *)0x0) {

LAB_00112b2c:

/* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

FUN_00107193(1,4,&PTR_s_/build/rustc-1.89.0-src/library/_0017df00);

}

*puVar10 = 0x6e69616d;

FUN_00134b20(pcVar18,ppVar6,puVar10);

}

}

uStack_80._0_4_ = 0x8000004;

local_108.__align = (long)FUN_0014fb00;

sigaction(7,(sigaction *)&local_108,(sigaction *)0x0);

lVar9 = *(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + -8);

lVar11 = DAT_0017fb08;

}

else {

lVar9 = *(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + -8);

lVar11 = DAT_0017fb08;

}

_DAT_0017fa58 = param_2;

DAT_0017fb08 = lVar11;

if (lVar9 == 0) {

do {

if (lVar11 == -1) {

/* try { // try from 00112a54 to 00112b41 has its CatchHandler @ 00112b44 */

FUN_0010e5c0();

goto LAB_00112b42;

}

lVar9 = lVar11 + 1;

LOCK();

bVar19 = lVar11 != DAT_0017fb08;

lVar4 = lVar9;

if (bVar19) {

lVar11 = DAT_0017fb08;

lVar4 = DAT_0017fb08;

}

DAT_0017fb08 = lVar4;

UNLOCK();

} while (bVar19);

*(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + -8) = lVar9;

}

DAT_0017fac0 = lVar9;

FUN_0010f340(FUN_0010fec0);

if (DAT_0017fa08 != 3) goto LAB_00112aa3;

goto LAB_00112a10;

}

local_110 = (void *)0x0;

local_68 = 0;

local_118 = pthread_attr_getstack(&local_108,&local_110,&local_68);

pvVar2 = local_110;

if (local_118 != 0) goto LAB_00112aea;

local_114 = pthread_attr_destroy(&local_108);

if (local_114 == 0) {

if (uVar8 == 0) {

FUN_001079d0(&PTR_s_library/std/src/sys/pal/unix/sta_0017e168);

goto LAB_00112b42;

}

if (((ulong)pvVar2 | uVar8) >> 0x20 == 0) {

uVar15 = ((ulong)pvVar2 & 0xffffffff) % (uVar8 & 0xffffffff);

}

else {

uVar15 = (ulong)pvVar2 % uVar8;

}

lVar9 = uVar8 - uVar15;

if (uVar15 == 0) {

lVar9 = 0;

}

ppVar6 = (pollfd *)((long)pvVar2 + lVar9);

pcVar18 = (code *)((long)ppVar6 - uVar8);

goto LAB_00112832;

}

ppuVar16 = &PTR_s_library/std/src/sys/pal/unix/sta_0017e138;

piVar17 = &local_114;

}

local_60[0] = 0;

FUN_0010e47f(piVar17,local_60,ppuVar16);

LAB_00112b42:

/* WARNING: Does not return */

pcVar18 = (code *)invalidInstructionException();

(*pcVar18)();

}

This decompiled function is the program startup/initializer, not the user main. The pseudocode shows classic runtime and platform setup: it calls poll/fcntl/open64 to check/initialize file descriptors, installs signal handlers (sigaction / signal), calls sysconf and pthread_getattr_np to query thread and stack info, initializes libc/Rust runtime structures, sets up thread-local data, and invokes runtime callbacks (functions like FUN_0010f340, FUN_0010fec0, FUN_0010e5c0, etc.). The many DAT_00... globals are runtime state and library pointers (e.g., pointers to Rust std internals). Warnings like Type propagation algorithm not settling and the undefined8 return type are Ghidra’s decompiler telling you it could not precisely infer high-level types common in compiler-optimized startup code : (

Another useful step in reverse engineering, especially when the decompiled code looks noisy or unclear, is to inspect the strings embedded in the binary. Strings often reveal crucial hints about program logic, such as messages printed to the console, function names, file paths, or even the flag format

Looking at the strings we see a hint to the flag

Lets move onto the looking at the flag functions .

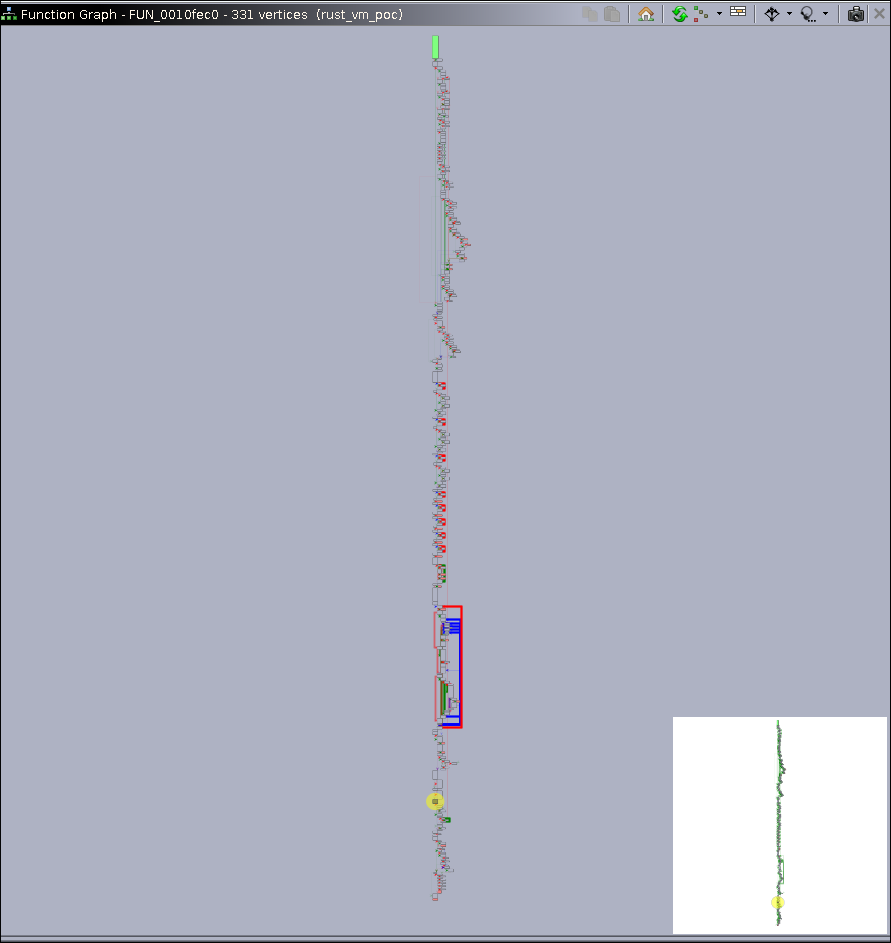

We see a function that has something called flag_generator and in the huge dissass we see PTR_s_Execution_finished._0017baf8 . So this might be the main logic handling of the binary .

ALsooo investigating the huge dump we find , a function call to FUN_00113590 included a long embedded string containing a complete Python script. The script defines a function named generate_flag_part(seed), which takes an integer seed, converts it to bytes, computes its SHA-256 hash, and returns the first eight hexadecimal characters of the resulting digest. This pattern suggests that the binary relies on Python code execution to dynamically produce a portion of the final flag

c

FUN_00113590(&local_248,

"

import base64

import hashlib

def generate_flag_part(seed: int) -> str:

seed_bytes =

str(seed).encode('utf-8')

hashed_seed = hashlib.sha256(seed _bytes).hexdigest()

flag_part

= hashed_seed[:8]

retu rn flag_part"

,0xfa);

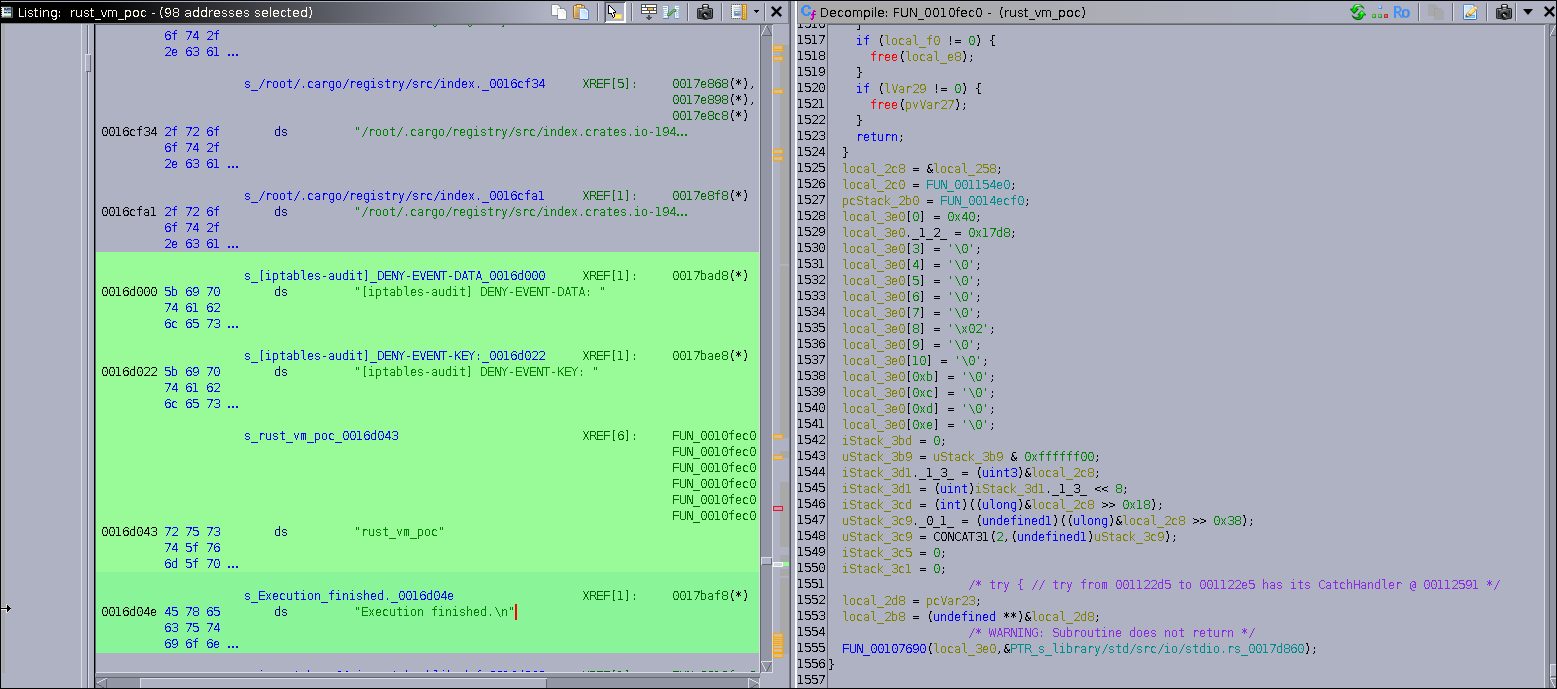

Investigating more through this huge rust dump we get ,

asm

s_[iptables-audit]_DENY-EVENT-DATA_0016d000 XREF[1]: 0017bad8(*)

0016d000 5b 69 70 ds "[iptables-audit] DENY-EVENT-DATA: "

74 61 62

6c 65 73

s_[iptables-audit]_DENY-EVENT-KEY:_0016d022 XREF[1]: 0017bae8(*)

0016d022 5b 69 70 ds "[iptables-audit] DENY-EVENT-KEY: "

74 61 62

6c 65 73

s_rust_vm_poc_0016d043 XREF[6]: FUN_0010fec0:00111b3e(*),

FUN_0010fec0:00111b45(*),

FUN_0010fec0:00111b8e(*),

FUN_0010fec0:00111c24(*),

FUN_0010fec0:00111c2b(*),

FUN_0010fec0:00111c74(*)

0016d043 72 75 73 ds "rust_vm_poc"

74 5f 76

6d 5f 70

s_Execution_finished._0016d04e XREF[1]: 0017baf8(*)

0016d04e 45 78 65 ds "Execution finished.

"

63 75 74

69 6f 6e

The "[iptables-audit] DENY-EVENT-DATA: " string is part of a static message table that FUN_0010fec0 uses to log results. Because the same codebase embeds a Python snippet that computes generate_flag_part(seed) and also contains the "Execution finished." message, the evidence indicates the program executes the Python/VM code and then logs its output using these prefixes. By tracing references from the pointer table into FUN_0010fec0 and inspecting the buffer written by the Python runner (the &local_248 passed to FUN_00113590), we can capture the generated segments and reconstruct the full flag also :) it provides the keyword, iptables-audit, needed to find the messages. Second, the presence of separate DATA and KEY fields is a massive hint that the flag is encrypted

Lets turn to analysing the system logs now .

journalctl is a command-line utility used on Linux systems that use systemd. It reads and displays logs that are collected by the systemd journal, which is the central logging system for systemd-managed systems.

Unlike traditional text logs (/var/log/syslog, /var/log/messages), the journal stores logs in a binary format, allowing structured queries, filtering, and metadata access. It includes not only messages from the kernel and services, but also stdout/stderr of systemd services

python

import base64

import binascii

encrypted_data_hex = "722e7e207155"

key_hex = "aff543c352c2"

# Decode, XOR, and Base64-encode

encrypted_data = binascii.unhexlify(encrypted_data_hex)

key = binascii.unhexlify(key_hex)

decrypted_data = bytes([d ^ k for d, k in zip(encrypted_data, key)])

flag = base64.b64encode(decrypted_data)

print(f"Flag: {flag.decode('utf-8')}")

### Flag: 3ds94yOX

PART-3

Step 1: Inspect the Hint File

The first file to examine is `hi.pskx`. Using basic tools like `strings` or `grep`, unusual sequences can be found. Searching for Base64-like strings reveals a hidden message:

bash

grep -a -oE '[A-Za-z0-9+/=]{12,}' hi.pskx | head -n1 | base64 -d

Decoded, this produces:

Bones align not for anatomy

This isn’t the final answer. Instead, it guides you to **look at bones or root nodes** in the Blender file to ultimately derive the archive password.

---

Step 2: Repair the Blender File Header (First 8 Bytes)

The corrupted Blender or `.pskx` file cannot open because the **first 8 bytes** are broken, which contain the **magic number and version**. Players must repair this to continue.

Solution:

1. Backup the broken file:

bash

cp broken.blend broken.blend.bak

2. Obtain a reference file (`ref.blend`) from the same Blender version or exporter.

3. Replace only the first 8 bytes using a hex editor or command-line tool:

bash

# Replace the first 8 bytes

dd if=ref.blend of=broken.blend bs=1 count=8 conv=notrunc

* `bs=1 count=8` → only the first 8 bytes are replaced

* `conv=notrunc` → keeps the rest of the file intact

4. Verify the file opens in Blender. The rest of the file remains untouched, allowing you to continue.

Fixing the first 8 bytes restores the file’s magic number and version, enabling inspection of root nodes to derive the next clue.

---

Step 3: Extract Root Node Values

Once the Blender file opens, examine **root nodes or bones**, which contain numeric values forming the zip password. This can be done inside Blender or with a headless Python snippet:

bash

blender --background repaired.blend --python-expr "

import bpy, json

objs={}

for o in bpy.data.objects:

props={}

try:

for k in o.keys():

if k!='_RNA_UI': props[k]=o[k]

except Exception:

pass

if props: objs[o.name]=props

print(json.dumps(objs))

"

Inspect the output for root node values. These numbers are combined to form the **zip password**, e.g., `498`.

---

Step 4: Unlock the Encrypted Archive

Use the password obtained from the root nodes to extract the hidden stego image from the archive:

bash

7z x challenge.7z -p498

Output:

Everything is Ok

Size: 5855446

Compressed: 5693434

We now have `lunee.jpg`.

Step 2: Analyze lunee.jpg

Let's check if there's anything hidden in this image using steghide:

bash

steghide info lunee.jpg

Output:

"lunee.jpg":

format: jpeg

capacity: 346.5 KB

Try to get information about embedded data ? (y/n) y

Enter passphrase:

embedded file "s3cret.jpg":

size: 64.5 KB

encrypted: rijndael-128, cbc

compressed: yes

Perfect! There's another file hidden inside. Let's extract it:

bash

steghide extract -sf lunee.jpg

Press Enter when prompted for the passphrase (no password needed).

Output:

wrote extracted data to "s3cret.jpg".

Step 3: Extract from s3cret.jpg

Now we have another image. Let's check if this one also contains hidden data:

bash

steghide info s3cret.jpg

It does! Let's extract it:

bash

steghide extract -sf s3cret.jpg

Again, press Enter for no password.

Output:

wrote extracted data to "flag.txt".

Step 4: Get the Flag

bash

cat flag.txt

**Flag:** `Cl41r3_3xp3d33 4sh3n_B0n3s33`

Solution Summary

bash

# Full solution one-liner

7z x challenge.7z -p498 && steghide extract -sf lunee.jpg -p "" && steghide extract -sf s3cret.jpg -p "" && cat flag.txt

part 1

c275036.89749.549105.207```

part2

```3ds94yOX```

part3

```Cl41r3_3xp3d33 4sh3n_B0n3s33```

The flag format is :

ctf{PART1_PART2_PART3}kernel